Written by Peggy Bell Hendrickson, Transcript Research

In Part I of this series, I discussed the importance of saving and storing your information so that you can access it again in the future when you need it. Part I emphasizes the concept of country folders as one way of organizing that information. Some general information was provided about methods for digitizing your resources.

This submission will actually take that idea a step further by showing you how to transition from folders to your own in-house database using a wiki.

My desire to create a wiki grew out of frustration with the many separate documents I was using to notate various aspects of evaluation. When conducting an evaluation, I initially had separate documents for equivalencies, grading scales, lists of resources, and others. I did not have a single source for indigenous terms so I was constantly looking up or transliterating the same words to ensure I could rely on translations. My repository of sample credentials was not organized in manner that made it easy to find what I was looking for quickly and easily. Different people could not access these documents at the same time, making it harder for collaboration and efficiency.

Also, I wanted to get everything out of my head (since it’s hard for other people to access that information!). I wanted a place to make notes about credentials I haven’t yet seen but heard about from a conference or conversation. I was eager to have a single source that I could utilize online that would allow for consistency in our approaches and strategies. Thus, our wiki was born!

Most of us are probably at least somewhat familiar with the concept of Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia. A wiki is a web-based content management system that runs using a wiki software platform, also known as a wiki engine. A wiki works like a blog in that the people updating the content do not actually have to know how to program or have much technical skill once the wiki engine is installed. Some wiki engines are open-source, meaning that they are free for use by the public as long as any changes made to the computer code are shared with the community, while others are commercial and charge a fee, in much the same way you can find free website creation software and fee-based website creation software. Typically, the open-source wiki engines are more likely to be programs that you run on your own server, while the commercial wikis are more likely to include hosting and are commonly known as wiki farms.

Wikis are in use by a number of industries and organizations. TV Tropes is an excellent example of a wiki about popular culture. Wiktionary is a free dictionary created by the Wikimedia Foundation. Scholarpedia is a peer-reviewed, open-access encyclopedia comprised of online academic articles. WowWiki is one of the largest wikis, about the popular massive multiplayer online game, World of Warcraft. Fan-based communities, or fandoms, have created thousands of wikis on topics such as Star Wars, Doctor Who, Pokemon, the Beatles, Marvel Comics, Lego Bricks, Sherlock Holmes, and any number of other entertainment sectors. WikiHow offers “How To” guides on thousands of topics.

The Wikimedia Foundation has also created WikiTravel, a free travel guide, and expanded that to WikiVoyage. OpenStreetMap is a variation that grants users access to use their maps. The Global Space-Based Inter-Calibration System uses a wiki as a repository for presentations, meetings, and research. Companies may use a wiki as a repository for product manuals, software updates, and trouble-shooting tips. Libraries find it easier to collaborate internally and externally using a wiki. Stamps of the World includes more than 300,000 wiki pages about stamp collecting. Wiki Educator helps people collaborate on developing open educational resources.

Government agencies such as the U.S. Office of Personnel Management or the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario use wikis. The National Cancer Institute hosts The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to help diagnose, treat, and prevent cancer. High schools and universities are using wikis to help students find information they need to register, pay for classes, or use school services. The French Advocacy Online Resources Wiki is dedicated to preserving French language as it influences identity and culture. Gamepedia is the largest video game wiki platform with hundreds of game wikis. You can find wikis focused on gardening, recipes, baseball, software patents, children’s books, song lyrics, Nordic names, risk management, aviation safety, and thousands of other topics.

One of the most interesting aspects of a wiki is that it is a collaborative resource, meaning that trusted users of your wiki can make changes to the content. In most wiki engines, you can set different security levels, so that some users can only view the information in the wiki (and maybe only some of the information at that), while others can edit and make changes, and an even smaller subset can delete content. Your institution may find that it is better to have other users submit suggested changes to a single super-user to limit the number of people who can edit the wiki. In addition, many wiki programs also have a way of restoring to previous editions as well as viewing all changes made to a single page.

Businesses are increasingly using internal wikis to document their in-house processes and information. Wikis are a great way of storing more than just your resource materials, however. They can also be a valuable tool for training. In our office, our country wiki pages also include links to the different country-specific YouTube videos we have created for in-house training purposes. We also have a separate section of our wiki that focuses purely on training, which includes training manuals, handouts, forms, videos, and supplemental information for evaluations as well as non-evaluation training on things like office standards on scanning, printing directly on envelopes, keyboard shortcuts, and other things that are useful but not always easy to remember. Since we have employees in different locations and have a weekly staff meeting/training using video conferencing software, we record our meetings and upload them to yet another page in our Wiki. That way, if someone misses the meeting, they don’t have to rely on the meeting notes or imperfect memories of those who attended.

Another great aspect of using a wiki is that a wiki is searchable. If all of your information is stored in individual documents, you have to know where the information is stored in order to access it. That sometimes means opening numerous documents and scanning through them individually. When your data is saved in a wiki, you can type your search criteria in the wiki search box, and it will search all of the information. This allows you to easily add information to your wiki that might be useful for a variety of countries, such as glossary terms, lists of abbreviations, and other resources that might not necessarily be tied to a single country or topic.

The actual process of creating a wiki can be as complicated or straightforward as your needs, technical expertise, and infrastructure allow. The actual process of building the wiki is beyond the scope of this article, which is focused on the desire for an in-house wiki and not on walking you through the steps to downloading and installing various programs. Using a search engine to look up ‘how to create a wiki’ will provide you with tutorials, videos, how-to instructions, and all the information you could need if your organization wants to run a wiki like DokuWiki, MediaWiki, or other self-hosted wiki.

Alternately, a wiki hosting service, or a wiki farm, such a Nuclino or Confluence can take care of the hosting and the technology aspect, and you would simply use their website for all of your informational needs.

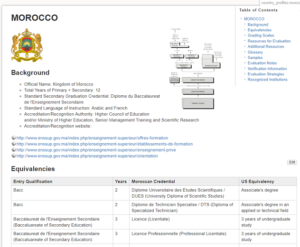

Once you decide on a wiki platform, you need to decide what you want to put in it and how you want to organize it. There are obviously a number of options, but I went for the most basic approach: I first made a list of all countries so I could create a separate entry for each of them. Within each country profile, I have created different sections: background, equivalencies, grading scales, resources, additional resources, glossary, samples, evaluation notes, verification information, evaluation strategies, and recognized institutions.

Let us briefly look at each of these categories. All of these categories are created with the intention of streamlining the evaluation process and maximize consistency among evaluators.

Background

In each country profile, I include a brief background of the educational system. This includes an image of the education ladder, an image of the national emblem/coat of arms, the official name of the country, the language(s) of instruction, the names of the recognition authorities, and other limited higher level information. When switching from one country to another, an evaluator can very quickly reorient to the next education system in this manner.

Equivalencies

The information in this section is fairly straightforward. This is represented by a table comprised of several columns: entry qualification, years, indigenous credential, and our in-house equivalency. Equivalencies are determined by a senior evaluator. We are careful to identify different equivalencies when the education system undergoes reforms or when the duration of existing qualifications affects our equivalency (such as credentials with the same name that have different standard lengths).

Grading Scales

At Transcript Research, we conduct a search on the grading scale for each credential. As the first step, we research the scale appropriate to that country, institution, level of education, and in some cases, faculty or field of study and date range. In our wiki, we maintain thousands of grading scales and our in-house conversions. We also save our research (degree plans, syllabi, catalogs, rules and regulations, information printed on the back of the transcript, etc.) to our cloud storage country folder so that we can access the details again in the future.

Resources

On our evaluation reports, we include a list of standardized resources that we utilize for evaluations for a given country. These are listed in our wiki in this section. We also add institution-specific information to the resources on our reports as needed.

Additional Resources

This section allows us to store data that may be used often but is not necessarily found elsewhere. This includes things such as outdated education ladders, national qualifications frameworks, links to university catalogs, news articles about new or upcoming education system changes, specialized resources that do not apply to all evaluations (medical programs, for example), and other information. This is also where I can save email conversations, internal notes, or other information that I think will be useful in the future.

Glossary

Each country profile has its own glossary. In our glossaries, we include credential names, column headers (first semester, second year, etc), academic terms (total credits, grade point average, etc), and indigenous grades. In addition, we include common courses and majors among others. Our wiki also has a centralized glossary for Arabic, French, Portuguese, Spanish, and numerous other countries that are used by multiple countries.

Samples

This is another self-explanatory section. We include sample credentials here. That way, I no longer have to rifle through conference handouts, newsletters, print and electronic publications, training materials, previous applications, and other sources of samples each time I want to look at documents from a particular country.

Evaluation Notes

We keep notes about how or why we evaluate some things the way they do. Some of this information goes into our evaluation reports, and some of it is purely so we don’t have to figure it out again. The kinds of notes can vary tremendously, from the difference between institutional and programmatic accreditation, to a summary of the education system to explain why we consider this particular credential to be compared to a US degree (or not), to an explanation of a unique grading program the applicant studied.

Verification Information

Transcript Research is very interested in ensuring that we conduct evaluations of authentic documents. To that effect, we have country-specific requirements for what types of documents can be submitted for evaluation. In addition, we try to send everything for verification. We are especially fond of electronic verification such as online databases and email, and we track that information for future use.

Evaluation Strategies

This section is another effort to enhance our consistency. Many countries have standardized credit systems used at the higher education level, so for those countries, we have a conversion table to ensure consistency. Likewise, a single university may follow the same credit system across all of its programs, so we store that information here to make it easier for the next evaluation. This is often especially helpful if a student has changed majors and may have significantly more courses or credits than they would otherwise. In a similar manner, if a student had not completed the program, it may be difficult to track down the number of units required for graduation, but if we had previously identified a credit conversion strategy for that institution, we have made things much easier for ourselves without having to go back through previous applications.

In addition, we have created hundreds of in-house training videos on evaluating different credentials, so we link to that information in the appropriate country profile. This is especially helpful for our junior evaluators but also for those challenging credentials that do not come around often enough to remember easily.

Recognized Institutions

This final section of the country profile includes a list of the recognized higher education institutions, the name of the higher authorities, and the link to their higher education authority information. We usually list both the indigenous name and an English translation. In this section, we are also able to track name changes, institutional mergers and closures, loss of accreditation/recognition, and other information. For those countries that also require programmatic accreditation for us to consider them to be comparable to regionally accredited institutions, we can also identify or link to the approved programs.

I have attached a screenshot of our wiki. It isn’t glamorous, but it is very easy to use and to store much of our information in away that, again, increases consistency.

See more from this Edition:

President’s Message: July 2017 Edition

Turkish Higher Education: July 2017 Edition

Turkish Council of Higher Education: July 2017 Edition

Evaluating Credentials with a Global Mindset: July 2017 Edition

TAICEP News and Updates: July 2017 Edition

Sample Russian Credentials: July 2017 Edition

Add to your Library: July 2017 Edition

Opinion: Theological Schools / Bible Colleges July 2017 Edition

Industry Information, News Articles and Journals and Publications: July 2017 Edition

Foreign High School Credentials – A Very Basic Overview: July 2017 Edition

In Memoriam: Drew Feder July 2017 Edition

2017 Conference: July 2017 Edition

Conference and Organizational Sponsors: July 2017 Edition